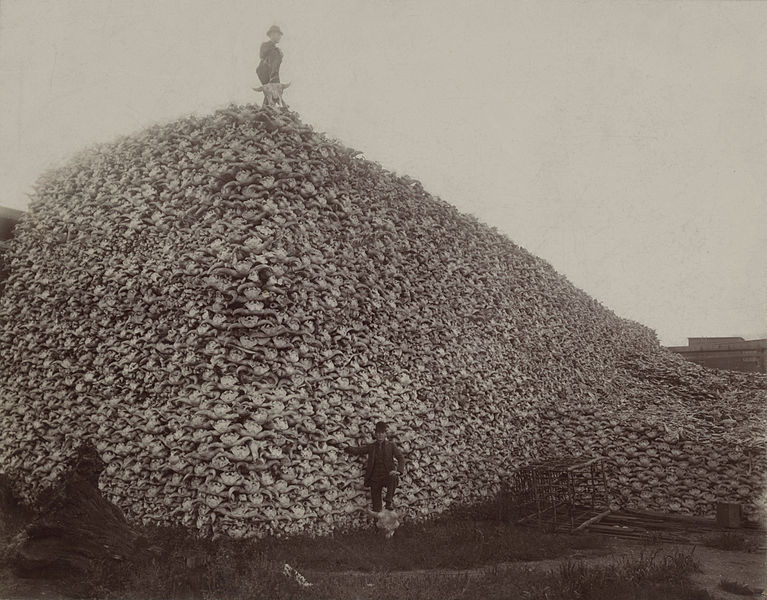

The almost complete and shockingly rapid elimination of the bison from North America occurred in less than 30 years following the end of the Civil War. The dramatic tale is well known: a population of tens of millions of keystone herbivores reduced to fewer than one thousand survivors. Lesser known, however, is the role that ranchers played in rescuing the bison from near-extinction. Somewhat ironically, those same ranchers whose cattle came to replace bison in the ecological niche of dominant herbivore were also instrumental in their salvation. And once again, almost 150 years later, it may be up to private ranchers to save the wild bison from ecological death.

In the 1880s, a small herd of 25 bison that was discovered in the remote Pelican Valley of what is now Yellowstone National Park was believed to be one of the only remaining wild bison herds. “This remnant herd and other scattered survivors might eventually have perished as well had it not been for the efforts of a handful of Americans and Canadians,” writes historian Andrew C. Isenberg in his book The Destruction of the Bison. “These advocates of preservation were primarily Western ranchers who speculated that ownership of the few remaining bison could be profitable.”

In fact, nearly all of the bison that today inhabit government parks and conservation herds (including Yellowstone National Park) are descendants of the five original herds founded by ranchers: the Charles Goodnight herd in Texas, the Alloway-McKay herd of Canada, the Dupree-Philip herd of South Dakota, the Pablo-Allard herd of Montana, and the Jones herd of Kansas and Oklahoma. Creating these foundation herds most often involved separating a small group of wild calves from a herd and capturing them. As tempting as it is to exalt these men (who several historians have argued were actually motivated to save the bison by the persuasion of their wives) as the inaugural champions of private-land conservation, their aspirations were largely economic.

The desire to combine the hardiness and resilience of the wild bison with the more commercially-favorable traits of cattle (like meat production) led to much of the initial crossbreeding that occurred on the ranches where the first bison herds were established. Undoubtedly, these early crossbreeding programs are to blame for many of the genetic challenges that plague wild bison herds to this day. Still, were it not for western ranchers like Charles Goodnight and Buffalo Jones–however misguided their intentions–the American bison just might have been erased from the continent, irreversibly. Even before ranchers began to understand themselves as ecologically-minded stewards of the land, their profit-driven work as cattle producers mingled with conservation in powerful ways.

Space and grass: a shared need for prairie

The historical relationship between American ranchers and the American bison is complex and thorny. Once at odds as competitors for grass, the rancher and the bison have more in common than one might expect, and might be better understood as allies in the restoration of the lost landscape of the once-great grasslands of America. First, both ranchers and bison are often misunderstood by the general public. Cattle ranchers and wild bison figure prominently in the public imagination of the “American West.” Caught up in a blurry nostalgia for the rugged, mystical frontier, the prairie dust kicked up by the clammer of hooves and the smoke exhaled by a hot branding iron does much work to obscure the true facts of life.

For example, bison are often seen as aggressive, deadly animals, and their sheer size and the speeds they can achieve in flight instill a misplaced fear in humans. In the same vein, ranchers are all-too-often represented as uneducated, cold, and environmentally-destructive men (and often incorrectly only men), with no regard for the land other than as a means for producing cattle. Due to the widespread alienation of the average American from the ways in which their food is produced and the land upon which it relies, ranchers and bison alike are the subjects of pervasive assumptions. The bison and the rancher both stand as powerful symbols of the American West and the rugged, individualistic, hypermasculine, pioneering spirit of the frontier myth that infuses our national identity to this day. Reproduced in dime novels, western films, art, music, and popular culture, the bison and the rancher simultaneously exist in material reality and in a fantastic dream from which America still has not awoken.

In addition to sharing the burden of false impressions, ranchers and bison both remain threatened in various converging ways. Ranchers’ access to the expansive lands they rely on—both public and private—has always been the focus of intense debate. The threat of exurban development, subdivision, and the shouts of anti-grazing environmentalists who cry for the removal of livestock (and ranchers) from public lands has been omnipresent throughout the history of ranching in the West. As a result of the pull it exerts on the public imagination, ranching attracts attention and scrutiny from a wide array of stakeholders, many of whom have an understanding of the western landscape based purely on the mythopoetic image of the cowboy. In reality, just by continuing to occupy land as a working landscape, ranchers are important agents of open space preservation, and their stock–be they domestic cattle or wild bison–are important agents of grazing, a critical ecological disturbance that helped create and maintain grassland ecosystems for thousands of years. Furthermore, the number of operating ranches and farms across the United States has been dropping steadily and dramatically over the last several decades. The median age of a principle beef cattle rancher is 58. Many family farmers and ranchers are failing and being forced to sell their land. Between 2012 and 2016, an average of 191 American farms and ranches were lost each week.

The primary threat to the American bison, much like the rancher, is related to the ever-shrinking availability of suitable habitat. The bison is the largest extant land mammal in North America, and their range once covered nearly the entire continent. Because bison migrate, not only seasonally but also in response to drought and fire, they require massive, contiguous tracts of land to survive unmanaged in the wild. Such landscapes, carved up and truncated by an exploding human population are increasingly only the stuff of geographic memory.

The introgression of cattle DNA into the bison genome also threatens the health of wild bison populations, an enduring legacy of crossbreeding attempted by those very same ranchers who saved the last bison from extinction in the wild. Many of today’s wild populations suffer from what population geneticists call “founder effects.” All five foundational private herds are suspected to have descended from less than 100 wild-caught founders (the remnants of a breeding population that once numbered in the tens of millions), leading to a severe genetic bottleneck and the loss of genetic diversity.

It is often assumed that the bison is no longer threatened because the population has rebounded so significantly. However, of the 500,000 or so plains bison on the North American continent today, it is estimated that over 93% are raised for commercial production and treated as livestock; fewer than 30,000 live freely as wildlife. In this sense, the plains bison as a wild creature, in all of its historical ecological integrity, remains extremely threatened. Years of artificial selection in commercial bison breeding programs have also increased the prevalence of non-adaptive traits, such as docility and meat production, that might damage a bison’s chance of survival in the wild. Ranchers have succeeded in saving the bison as a species for commercial production, though it remains to be seen if they will be saved as a wild species for ecological restoration.

Perhaps the most important threat facing the bison is ecological extinction. The rapidly growing population of bison raised in the livestock industry will ensure that the bison will not go extinct. The ecological role that bison played in grassland ecosystems, however, is still very much at risk of being lost, and is not so easy to recover. Bison currently occupy less than 1% of their original range, and the incomprehensible reduction of a historical breeding population of tens of millions of animals to a mere tens of thousands, mean that the cascading effects of a keystone herbivore on the ecosystem are likely no longer made possible. This is what conservationists refer to as “ecological extinction;” in essence, because of the miniscule size of the current range and population of wild bison relative to its once-greatness, bison are unable to fulfill the ecological role they once played as a dominant grazer and agent of disturbance. Especially within landscapes from which large predators have long been extirpated, finding unfenced areas for bison to live without human management is near impossible. Dale F. Lott, a behavioral ecologist and natural historian points out that the plains bison is the “only wild animal in the United States that is not allowed to live as a wild animal—live outside parks and refuges—anywhere in its original range.”

The one common denominator among the threatened, misunderstood existence of bison and ranchers alike is that primal point of contact: the very ground where boots and hooves meet the prairie earth, where the body is caught by the delicate web of the ecosystem of which he has become a part. They both need land. The land’s the thing. They require wide, open, contiguous landscapes, undisturbed by modern development and conversion; the kind of places that are increasingly few and far between.

The future of the MZ herd

Today, The Nature Conservancy’s Medano-Zapata Ranch, which is managed by Ranchlands, plays host to one of the largest and most genetically pure herds of wild plains bison in the United States. The success of the conservation project of restoring bison to the southern Rocky Mountains is owed to the unprecedented partnership between the Nature Conservancy and Ranchlands. As unlikely allies on the frontlines of a new wave of collaborative conservation in the American West, Ranchlands and TNC have created a model that is not only ecologically restorative, but also economically self-sustaining. Bison meat can be sold for a higher price than beef, and conserving the wild bison as a means of production offers ranchers a unique opportunity as stewards of big landscapes.

But despite all of its success, the future of the bison herd at the Medano-Zapata Ranch is uncertain. When the Medano-Zapata Ranch was first purchased by TNC in 1999, it was just one part of a larger landscape-scale conservation project to designate and protect several hundred thousand acres of land in the northeast unit of the San Luis Valley known as the Great Sand Dunes Conservation Area. From the outset, part of that deal that was struck between TNC, private landowners, and the federal government was that the southern boundary of the National Park would eventually become Lane 6, the highway that currently divides the Medano from the Zapata portion of the ranch. So, the northern half of the Medano-Zapata Ranch, which is home to the 1800 or so head of wild bison managed by Ranchlands, will soon become a part of Great Sand Dunes National Park, and the National Park Service will take over management. While the National Park Service will undoubtedly work to protect the Medano Ranch in perpetuity, the bison who now call that land home may not always remain as they are today.

The northern San Luis Valley is dealing with an overpopulation of elk, who compete with bison for habitat. Because the resident bison are seen as easier to control than the elk population, NPS would prefer to remove the majority of the bison herd to avoid overutilization. According to the NPS’ Ungulate Management Plan for the park, transferring management of the Medano and the bison herd will occur over a transition period of 5-7 years. Several alternatives have been proposed to manage elk and bison in the park, but the NPS’ “preferred” alternative involves reducing the bison density to a range between .01 and .001 bison per acre. In other words, “a population goal of 80 to 260 animals” within the existing bison fence.

Conservation biologists have determined that a minimum effective population of 1000 bison is necessary to avoid inbreeding depression and the loss of genetic variation in wild herds. So, while the existence of any bison in the San Luis Valley is a success, such a small remnant herd in the park would not retain the genetic and ecological integrity that the herd boasts today. One of the only conservation herds of plains bison in the United States with a sufficiently large population will be fractured.

The continued presence of wild bison in the Southern Rocky Mountains is likely not in jeopardy. Still, of the 1800 bison who currently roam the Medano under Ranchlands’ and TNC’s stewardship, only one or two hundred are destined to remain. What, then, will happen to the rest? Where will they go?

For those bison that are removed, their fate hangs uneasily in the balance, faced once again with a radically altered landscape that struggles to make room for their existence. Just as the dwindling populations of wild bison that remained at the end of the 19th century were saved by ranchers, the wild bison herd of the Medano can be saved by Ranchlands. Given the right piece of land, suitable for a large conservation herd of bison and small team of conservation-minded ranchers, Ranchlands, TNC, and others are in the preliminary stages of looking at the possibility of creating a fund whereby people can invest or make a donation toward the purchase of a ranch that would be the home for this herd in perpetuity. In addition to solving the bison dilemma, it would allow the unique partnership between Ranchlands and the Conservancy to provide oversight to the herd long into the future. In a curious repetition of history, the rancher and the bison might just be able to save each other from ecological extinction, as a wild species, as an archive of wild knowledge, of intimate relationships to land, and of the wild roots of the American frontier.

Not any piece of land will do, unfortunately. Ranchlands requires a special kind place to allow these bison to roam, a large enough landscape to support a sufficiently large population of bison (at least one thousand), to preserve the genetic diversity of the herd and to allow for adaptation to future changes in the environment. The bison of the Medano-Zapata Ranch need a home, and Ranchlands is working hard to find a landowner that is willing to help provide them one.

The bison is the quintessential rangeland inhabitant, an embodied parable of how consumption and conservation can–and must–achieve harmony. The uncertain future of the Medano-Zapata Ranch bison is but the last sentence in the final chapter of a book as old as time itself. The epic story of the earth’s grasslands has been written for thousands of years in hoof-prints and wind gusts, and it continues. The 30 million bison that once saturated the continent filled the herbivorous niches left vacant by the great Pleistocene extinctions that occurred over ten thousand years ago. Born of great extinctions, drought cycles, and heat waves, the prairie rolls on through deep time as the lost sea of grass, once maintained by Woolly Mammoths, then bison, and now cattle, may once again be a place where the great wild bison, and so too the western rancher, can live and breed and die. So long as we find a home for these animals, the rancher and the bison may continue to coevolve, and through a symbiosis achieve collective immortality.

Leave a comment