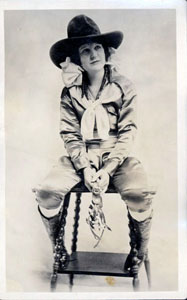

Dorothy Morrell at 1920 Cheyenne Frontier Days, before women were barred from the sport.

She wore a large-brimmed beaver hat, fringed gloves, a handmade western blouse, custom boots, and jodhpurs. Sometimes she’d add a wild rag, vest, chinks, or woolies. She’d pin down her hair, secure her gear, and pace around in her preferred pre-ride ritual. Next, she’d mount up on her bronc, and begin her ride. Her sorrel gelding bounded forward, wringing his body like a wet rag, eyes-rolling, squealing with nostrils flared. Suddenly everything became primal and basic— stay on.

The year is 1922 and Bonnie McCarroll is the top female bronc rider in the nation. She made rodeo history by placing first at the prestigious Cheyenne Frontier Days, as well as the Madison Square Garden Rodeo. But Bonnie is not an anomaly. Women have been professionally competing at rodeos since 1903.

Bonnie McCarroll sitting with spurs, 1924.

Rodeo roots span back to the 16th century, when Spanish conquistadors introduced cattle to the Americas. By the mid-1800s, the common ideation of the American “cowboy” had begun. A surplus of feral cattle and horses after the Civil War led to a brief but lucrative cattle kingdom. As the demand for beef in the East was growing, famed trails trodden by Charles Goodnight, Oliver Loving, and John S. Chisum were formed. This flourishing industry created a unique subculture: men and women mastering their riding and stockmanship skills and competing for extra cash. “Bronco-busting” contests were recorded as early as 1869 in the Colorado Territory.

Though women were rarely hired as cowboys, they were born into ranching families, and proved to not only keep up with the cowboys, but often surpassed them. Women participating and competing in rodeo events was pragmatic; they had been doing it for decades. These were the daughters of the open range. They had started colts, roped mavericks, and castrated livestock.

Women branding in the San Luis Valley, 1884.

Fanny Sperry Steele, the acclaimed bronc rider in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, grew up breaking horses at her families Herrin Ranch in the Beartooth Mountains of Montana. In 1903, 18-year-old Lucille Mulhall broke countless steer-roping records against her male competitors. Annie Shafer rode bucking steers and broncos before the age of 14 at her father’s Arkansas ranch. Women competed for purses equal to men. By 1928 one-third of all rodeos had female events.

Everything changed in 1929. On the day she intended to retire, Bonnie McCarroll died from injuries sustained at the Pendleton Round-Up. She was thrown from her horse, knocked unconscious, and dragged around the arena from her stirrup. As the days of the range were becoming a dusty memory, so was the perceived place of women in rodeo. McCarroll’s death was the final summation to the growing opposition against female bronc riders.

Bonnie McCarroll thrown from Silver, 1915, 14 years prior to her fateful ride.

You just forget about being scared when you a ride a bucking horse. Think of staying on top and perhaps you shall, some of the time. Just be thankful if you’re able to get up and try it once more.” Fannie Sperry Steele, 1975 (age 88)

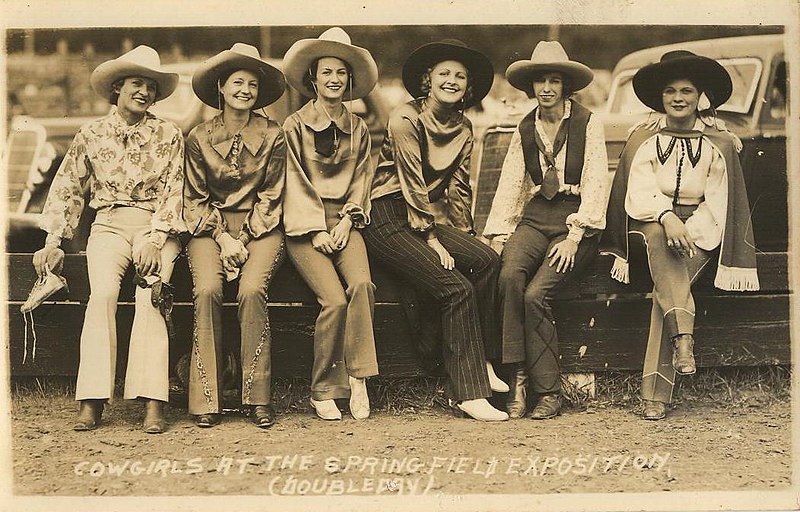

In the subsequent years, women’s roughstock events were quickly removed from all mainstream rodeos. By the 1930s traditional gender roles were encouraged. Women began being celebrated more for their aesthetics than their athleticism. By the 1940s, famed western singer Gene Autry became a major rodeo promoter, and cut female bronc riding from his New York and Boston rodeos. Women were spurred to transition from roughstock to barrel racing and rodeo queen pageants.

Cowgirls at the Springfield Exposition, circa 1930.

In 1948, as the gender divide deepened, the Girls Rodeo Association was formed. Comprised of skilled ranch women who had taken over family operations during World War II, the GRA was formed to offer a greater diversity of events (and payout) to the modern cowgirl. In 1981, the organization became the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA). The earliest pioneers of the GRA were ropers, bronc riders, and barrel racers, dedicated to offering greater opportunities in the arena.

Despite efforts in recent years to include women in roughstock events just as they were in the early 20th century, progress on a larger scale has been relatively stagnant. Make no mistake, there has been a resurgence in the quiet corners of America— small town roughstock events, female bronc riding tours, television programs, and well-attended rodeo schools. However, the largest and best paid rodeos primarily limit women’s events to barrel racing and breakaway roping. Though impressive events in their own right with incredible athletes, there is a growing interest among young female riders to have roughstock options on a National scale. And why shouldn’t they? After all, cowgirls have been covering broncs for centuries.

Leave a comment